Doc Hoc: Grading the SAE controversy responses

It has taken me a while to process the varying responses to the recent racist sing-along on a chartered bus carrying University of Oklahoma Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity members and their dates on an extremely memorable day.

As you know, a short video surfaced of the song, which included the n-word and referred to lynching, conjuring up this country’s sordid history of slavery. Afterwards, OU President David Boren kicked the fraternity off campus, expelled two of its students and opened up an investigation into the incident.

As OU made the national television news night after night last week, there were a myriad of responses on social media, in television interviews and newspapers and on numerous blogs.

Here’s a list of some responses, in order, that I’ve ranked worst to okay to good to ambiguous to best.

First Responses: D

There were at least two major first responses to the incident.

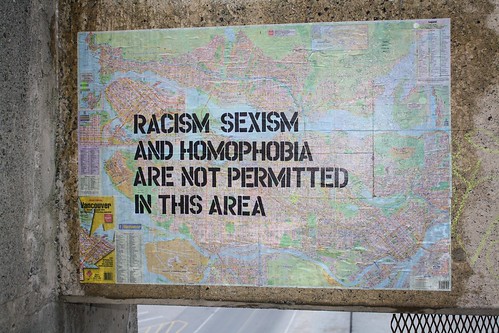

One of the overall first responses essentially brushed it all off as stupid college student behavior and argued that the media was paying too much attention to it. This response essentially ignores this country’s history of slavery, followed by systemic racism that has never ended. Except for what white supremacists probably thought about the event, this response was the most widespread worst response. I’m sure some of the people who argued this initially changed their minds as the hate bus week unfolded, but the gut reaction to qualify this type of behavior is part of the reason why racism persists. Racism is never just a prank. It’s hatred and vile.

Another response that surfaced on social media—and this was actually my first knee-jerk response—is the argument that Oklahoma is a cesspool filled with hateful bigots and that this state in which we live is an embarrassment to all of humanity. Those with this opinion conflated this incident with other actions, particularly with what’s been going on at the state Capitol this legislative session. Obviously, there are fallacies here. For example, I know a lot of people here in Oklahoma yet I don’t know personally a single racist. We’re all now connected to a larger global community, anyway, through the Internet and other technologies. I communicate with people and have friends throughout the world. The idea that a state should or does define a person doesn’t hold much credence with me. The racist song, in particular, or Oklahoma, in general, doesn’t define me or my family or my friends or my colleagues. So this response, perhaps more understandable than brushing off the event as immature college behavior, was overstated and fallacious, too. This could have happened elsewhere. There are SAE fraternities across the country. Oh yeah, the two young men expelled from OU were actually from Dallas. If it’s a specific Oklahoma problem, it’s a specific Texas problem, too.

-

Boren’s Response: C? B-?

I’m ranking Boren’s response in the mid range. Boren had to do something significant within the media storm, and I agree in principle with the expulsion of the two students and eviction of the fraternity. I think Boren also made it clear that racism would not be tolerated on campus. Yet, as I’ll note further along in this post, he acted so swiftly and dramatically that it raised questions about students’ rights and freedom of speech. The university’s image is important, but at what cost? Could Boren have waited a couple more days before he officially expelled the students, for example? The national SAE had already suspended the chapter before Boren ordered them off campus. Perhaps, Boren has more information about the fraternity that he’s not sharing, but the fact the members have hired an attorney is telling. Yet, even then, it doesn’t seem to me that an extended legal action against the university would be in the best interest of any student who participated in the sing-along. Was that Boren’s reasoning?

-

Striker Strikes: A

I liked OU football player Eric Striker’s response to the incident. Sure, his first public reaction through a Snapchat video was over the top and filled with profanities, but it encapsulated, and perhaps even contained on a community level, the anger caused by the incident. But after he made the video and, in the ensuing days, Striker apologized for his rant and calmly explained to the media the hypocrisy of bigoted fraternity members who supposedly support or act like they support the university’s football team, which includes many African American players. Was his the model response for anyone on the OU campus? I don’t know about that, but it was an immediate outburst of anger that then turned into something more productive later. I think that’s important. Get angry. Stay controlled. Take productive action and don’t resort to violence. But then we have to take into account OU football player Joe Mixon, the young convicted offender who broke bones in a young woman’s face because he got angry. He’s still on campus. SAE is gone. No one on the bus of hatred broke a woman’s face with his fist as far as I know.

-

Freedom of Speech Issues: B

Boren’s swift actions to expel the students and close the fraternity raised the issue over whether or not the students singing the racist song were protected by the First Amendment. I remain ambivalent about this issue, at least as it manifested itself in the media after the event. I’m very much in favor of freedom of speech, of course, but I wonder if this is an exceptional case that deserves more legal wrangling than a quick denouncement from the legal and academic establishments.

Essentially, some in the legal and academic communities, argued that, indeed, the students’ right to freedom of speech was violated by Boren. They were quite adamant about this, and I wound up in heated Facebook and personal discussions about this point. Many legal scholars and media law professors argue that racist speech in itself doesn’t necessarily arise to hate speech, as long as it isn’t specifically intended to cause violence. Boren said the sing-along caused a hostile learning environment, yet it was spoken off campus, and the students weren’t given due process BEFORE either they were expelled or kicked out of their residence. Those that argue that the speech was protected made it clear they don’t agree with racist speech, but that it’s the price we pay for freedom of speech.

My argument is that the specific issue about student speech is more nuanced and complicated, and that perhaps a lawsuit could help clarify whether racist speech, in particular, a century and half after the American Civil War, is still protected, especially when affiliated with college campuses, our beacons of knowledge. In other words, does racist speech affiliated with a college arise to some level at which it can’t be tolerated or guaranteed because of the college’s academic mission? In this regard, the racist song wasn’t necessarily hate speech in the prevailing judicial sense—though some might argue it did rise to that level—but instead represents a clear and existing threat to the stability and even viability of the university. Could it lead to changes in conduct codes at universities?

All this is moot, perhaps, because it seems unlikely to me most of the students involved in the incident, especially those two students expelled and identified by the media, would want their identities consistently revealed in a long, drawn-out legal action that could even wind up in the U.S. Supreme Court. I doubt any judge would conceal the students’ identities if they claimed specific harm and damages and their names would be all over the Internet along with the short sing-along video. The university could even consider counter suing on the grounds that the singing students have damaged its reputation or “brand,” thus lowering the financial worth of its degrees for all its students.

Non-Violent Protestors: A+

By far, the best response, and this included Boren and Striker as well, came from the non-violent protestors that marched on the university campus right after the incident to send the message that racism would not be tolerated. This type of non-violent protest is not only guaranteed by the First Amendment, but also is crucial in advancing the larger awareness about the existence of racism in our culture and in supporting the academic mission of OU or any university.

The civil rights movement in this country in the mid-twentieth century was founded on non-violent protest. Unarmed, peaceful people were killed for speaking up against injustice. This country has come a long way in regards to racism since the Selma to Montgomery marches in Alabama in 1965, but, as the OU incident and other recent acts of nationwide social injustice prove, it still has a long way to go.

Kurt Hochenauer is an English professor at the University of Central Oklahoma and the author of the Okie Funk blog. He’s adamantly against racism and other forms of bigotry.

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter